Guna

The sea-dwelling mola designers of San Blas Islands

Most of the nearly 400 islands of the San Balas archipelago, off the coast of the Isthmus of Panama, are just shallow swathes of land barely sticking out of the waters of the Caribbean sea. Among them, only 49 are home to the majority of the 70,000-strong population of the Guna (also known as Kuna) people.

Soon, the islands’ inhabitants may be forced to join their tribesmen living on the mainland, as the rise in sea levels caused by global warming is endangering their existence.

It wouldn’t be the first time that the Guna have had to relocate because of natural or political factors. Previously, they lived in the coastal mountains, but then moved to the coral islands in the mid-19th century after decimation by mosquito-spread diseases such as malaria and yellow fever.

However, the mountains were also only a stopover in their journey from what is now Northern Colombia and the Darién Province of Panama, where they resided at the time of the Spanish invasion. It was the conquistadors and hostile indigenous tribes that pushed them westwards towards the sea.

Looking further back to centuries before, the Guna were part of the Chibchan migration that descended on the region from Central America. Today, they are concentrated in three provinces which have the status of autonomous reservations: the largest reservation is called Guna Yala (meaning Guna Land in Dulegaya, the Guna language).

The Guna people are a close-knit tribal society that is divided into communities, each led by a leader called saila. He is both a political and spiritual authority, administering the daily affairs of the community and acting as a repository of the tribe’s wisdom, legends and laws. Those are usually transmitted in the form of songs sung in Onmaked Nega (Congress House), a special building for meetings and decision-making.

At the centre of the Guna belief system lies a god named Pab Tummat and his spouse (Nan Tummat), from whom all things derive. The course of life of each individual is predetermined by a spiritual headdress (kurguin), which is placed on the head at birth by the great grandmothers (Mu Tummagan).

Life in San Blas

The Guna continue to live a very much aquatic existence – even on the mainland, their villages tend to consist of houses built on stilts over coastal marshes. They go fishing in their canoes, diving in search of crabs, octopuses and lobsters. The Guna have always been keen traders, having a tradition in commerce since they supplied pirates and buccaneers with various resources. On the land, this is complemented by collecting yucca, bananas, and, most importantly, cacao.

The group has a special, spiritual bond with the cacao – using it to make a beverage called Siagwa, which is a fundamental component of countless ceremonies and is believed to be a source of vitality. There are several varieties of Siagwa: pure Siagwanis (ground cacao, water and sugar), Siagwa Olligwa (ground cacao, corn and sugar), and Madun Siagwaba (boiled banana, ground cacao and sugar).

The Mola Patterns

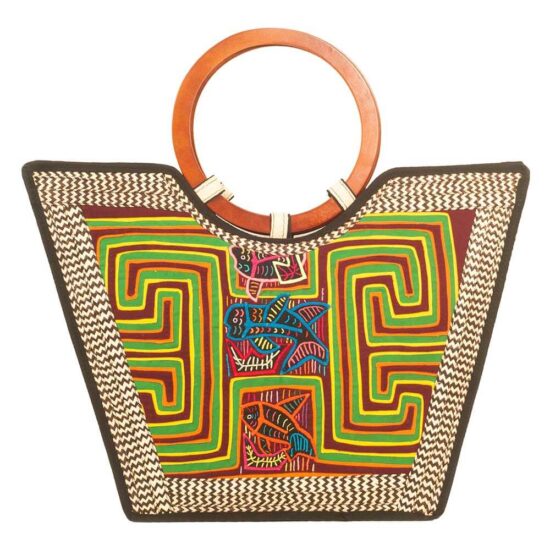

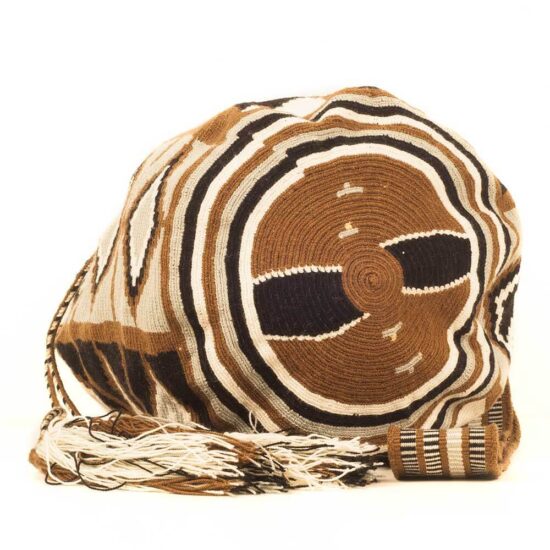

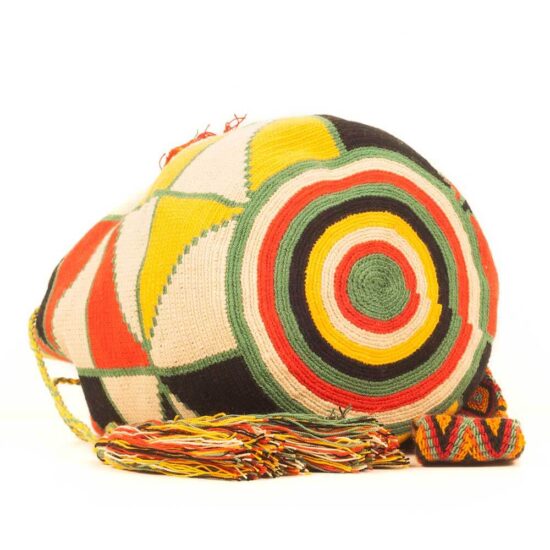

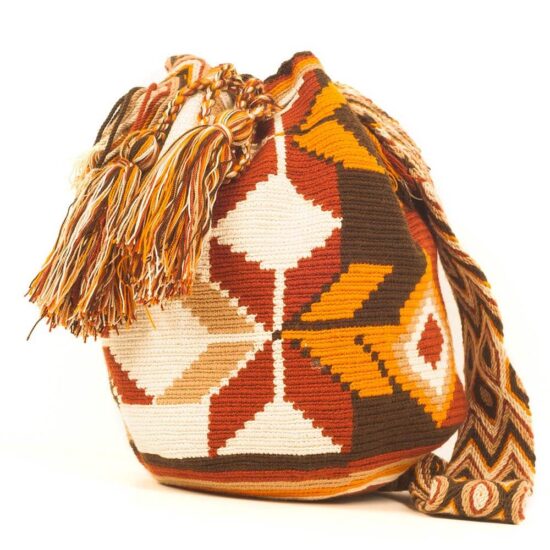

Mola (meaning clothing, in particular, blouse) are the embroidered, multilayered textile artworks that are mainly used as decorative panels on the front and back of a woman’s blouse. They may appear on skirts, scarves or shirts as well as pillows, mats or even be framed and hung on the walls. As a garment adornment, they were first used some 150 years ago, but they had been practiced much longer in the form of body-painting.

As the Guna were in the past a nomadic people, they were less keen on creating long-lasting, sculptural or architectural forms of art, and so their primary form of visual expression came in the shape of body decoration. Only gradually, as they adopted weaving techniques and fabrics brought by the Spanish, they transferred the molas onto the textiles – with the designs being initially painted into the underskirt.

The molas consist of between two to seven layers of cotton pieces that are sewn together by appliqué. Their quality, apart from the beauty of the design itself, depends on the number of layers and the fineness of stitching – normally, the stitches are the same colour as the layer fabric, which in the best pieces makes them nearly invisible.

A large proportion of the panels depict plants or animals, while others focus on scenes of daily Guna life, and lifecycle events and myths. The oldest designs are those with geometric figures that date back to the times of the body painting. Many, however, are paradoxically influenced by Western culture – various political posters or crests, book and magazine covers, daily product packaging and even TV cartoons.

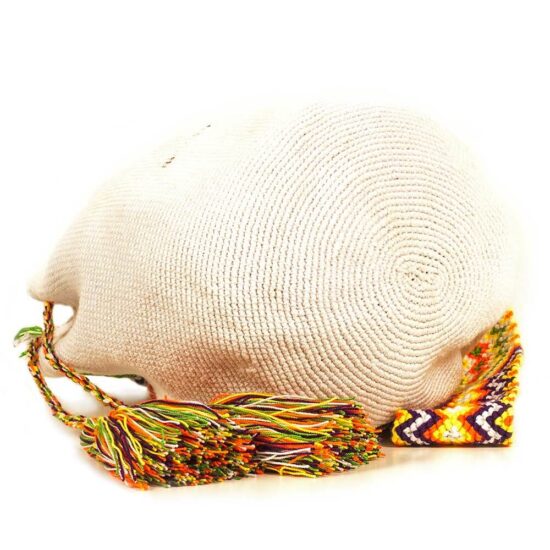

Molas were commercialised pretty early and selling them to outsiders is now a vital part of the Guna economy. The tribe was very successful in promoting them as their mark of identity, to the point where they became one of the visual representations of Panama as a whole, just like the Arhuaco knapsacks became the symbol of neighbouring Colombia.

Guna in Modern Times

Except for the initial skirmishes with the Spanish, the Guna managed to remain on the margins of the history. But when Panama separated from Colombia in 1903, their land got divided with a border and they found their political and national loyalties questioned.

By 1919, the Panamanian government commenced a harsh policy of forced assimilation and suppression of the indigenous culture. A ban was instituted on wearing components of a traditional Guna woman’s dress, leg and arm bindings, and nose rings. The tribal dances were prohibited, as well as drinking of alcohol – a fundamental element of various rituals and the spiritual life of the tribe.

After six years of what some call an ethnocide, a revolution took place in 1925 – the Guna attacked and took control of several islands, and a US-backed agreement was struck with the government, allowing the group to maintain their territory and self-governance.

Interestingly, it was during those years of struggle that the women’s dress came to prominence as a symbol of ethnic identity and political resistance. During and after the revolution, the tribal leaders instigated a revitalisation of the group’s traditions and the mola patterns came to the forefront of this project.