Wayuu

The Master Weavers from La Guajira

As the story goes, Irunuu was a young hunter of the Wayuu tribe. One day, while hunting for prey in the desert, he found a young orphan. The sight of the miserable, dirty child saddened him deeply, so he brought her back to his ranch (piichipala or miichipala), and asked his sisters to look after her and introduce her to the daily routines of the Wayuu women.

However, the sisters as well as the other members of the tribe took a dislike to the girl and mistreated her, denying her food and love, and Irunuu was forced to take care of her himself.

Shortly after the girl’s appearance, the sisters started to present Irunuu with chinchorros, blankets and wayucos (sashes), which were of a beauty and quality that had never been seen before in the village. Even though the sisters assured him that the fabrics were woven by them, Irunuu remained suspicious of their origin.

One night, he came home earlier than usual, and when he opened the door of his hut, he saw Wale´kerü (spider in Wayuunaiki / Goajiro, the Wayuu language) transformed into a beautiful maiden, pulling threads from her mouth and weaving them into the precious fabrics.

As he discovered their true origin, he found himself falling madly in love with the maiden, and drawn to her with some irresistible force he tried to embrace her. But, his arms grasped only shreds of a spiderweb – the maiden turned into a spider and disappeared into the branches of a tree that grew by the house.

She kept returning to the village though, and taught the women how to weave in exchange for their goats, donkeys, clothes and necklaces. This is how the Wayuu women learnt their craft.

Cabo de La Vela (Jepirra) is, in the Wayuu cosmogony, a liminal space where all the deceased gather before their final departure into “the unknown”, where the ancestors await.

The Wayuu Society

The Wayuu people inhabit the Guajira Peninsula that straddles the Colombian-Venezuelan border along the Caribbean coast. It is an arid, rough land that at times doesn’t see a drop of rain for three years or more. The scenery is captivating, dominated by the orange of the sand dunes, the crisp blue of the sky, and the ocean with snow-white patches of salt beds here and there.

Harsh sun creates stark contrasts of blinding saturated colours and dark black shadows. Water is scarce and poverty is rife – recent reports indicate that one to two children die in the area every week due to malnutrition and lack of drinking water.

Located at wide distances from one another, to avoid mixing of the goat herds, are rancherias (or caseríos) – small settlements of five to six houses – usually named after totemic plants or animals. The huts (piichi or miichi) within rancherias are made from yotojoro – a wattle and daub composed of mud, hay and dried canes; however, some have welcomed cement into their rancherias.

The Wayuu still retain their traditional social structure which, interestingly, is matrilineal – within the nuclear family, the children respond to the mother’s brother rather than their biological father. The maternal uncle is also the highest authority of the extended family. The women have a decisive part in many aspects of the clan’s life and have a very independent position within it. However, polygamy, occasionally practiced by the Wayuu, is restricted to men.

The group doesn’t have very formal institutions of social control, and its norms with regard to conflict-resolution are designed to re-establish the order and minimise damage to the social community, rather than to punish the offender. A crucial role in crisis situations is played by a pütchipüüi or palabrero – a skilled negotiator who brings the conflicting sides together and helps to resolve the issue.

Textile crafts and weaving skills have a paramount role in Wayuu society. These arts are considered to be a way of expressing life as experienced by the Wayuu and how they desire their lives to be. They are a symbol of creativity, intelligence and knowledge, and each fabric is infused with a part of their culture and tradition.

Kanasü, the geometrical patterns of the fabrics, are the very essence of the craft. In a similar fashion to those designed by the Arhuaco people, they are stylised interpretations of the tribe’s surroundings: animals, plants, astronomical objects and forces of nature. The complexity of the pattern determines the value of the piece, as much as the value of the weaver in the marriage market.

The Wayuu Weaving Techniques

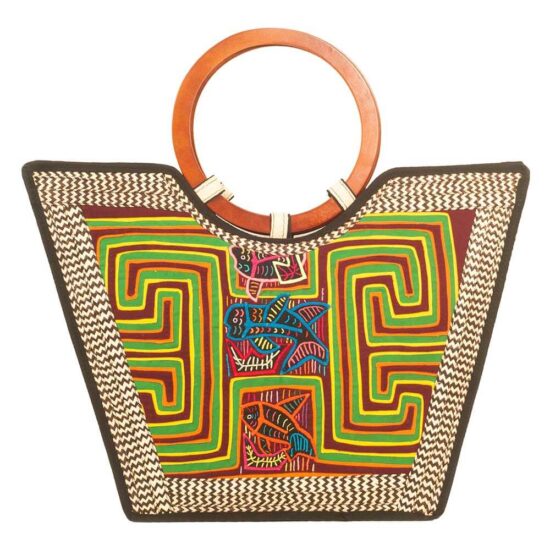

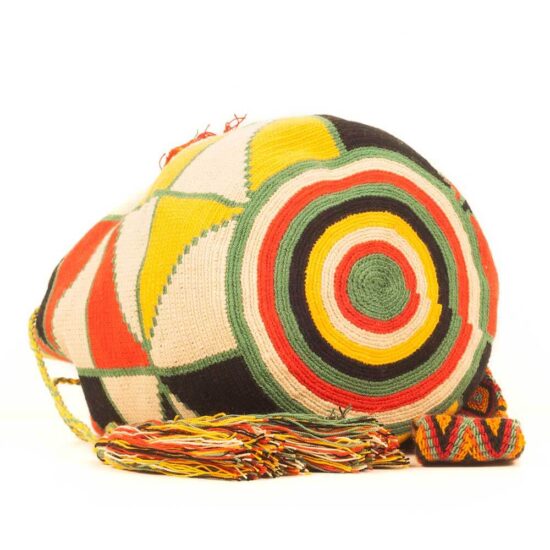

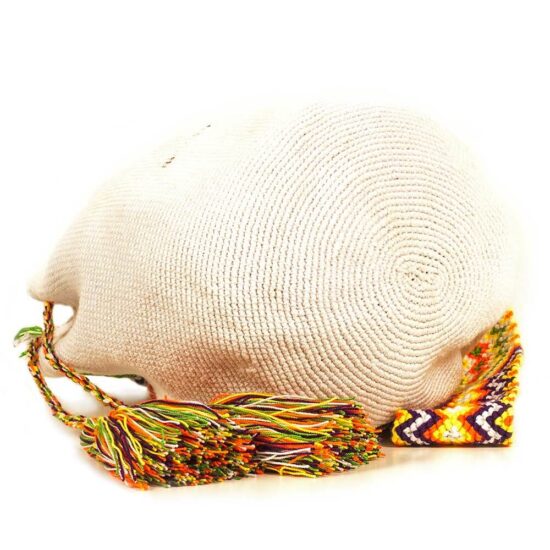

It is worth noting that there are several weaving techniques, and it is not as simple as the legend would have it. In recent years, the most common products to have achieved worldwide fame are the colourful Wayuu bags called Susu, which are crocheted, a technique considered to be entry-level. Interestingly, the Wayuu women learned crochet from the Capuchin nuns at the beginning of the 20th century. In addition to traditional geometric patterns and newly invented designs, they used the American DMC’s pattern books, which can be seen as a truly post-modern tale of a reverse cultural appropriation.

Originally, the fabrics were created from local cotton that was handspun and dyed with natural dyes, most often in tones of brownish-red, beige, blue, yellow, white and black. The vivid, saturated appearance, which the Wayuu bags are famous for, is derived from the synthetic yarns that are used contemporarily.

Adopting the new material, the Wayuu women mastered the art of composing daring and challenging, but harmonious and tasteful colour combinations. The Susu bag also reflects the harmony between a woman and a man, as it is the latter who makes the angular-patterned straps (gasa) that are attached to the bags in the final stage of production.

Becoming a Wayuu Woman

Traditionally, a Wayuu girl would learn the secrets of weaving during blanqueo – a period of between three months to one year, starting at the first menstruation. During this time, she would stay in a separate part of the house, only seeing the women of her closest family and undergoing a series of rites of passage.

The first several days would be spent in a hammock suspended high from the hut ceiling, observing a special purifying diet. Then, she would be ceremonially washed by her mother and her hair would be cut. Thereafter, she would spend months being taught the domestic chores, and, most importantly, the skills necessary to become a skilled weaver. After demonstrating the less challenging techniques of threading the mochila bags, she would move on to the more advanced art of weaving chinchorros, and finally, the hammocks.

Hammocks and Chinchorros

Chinchorros and hammocks are fundamental objects in the social and personal life of each member of the tribe – they are hanging beds in which the Wayuu rest, sleep, have conversations, receive visits, weave, procreate and give birth. Despite having the same function, chinchorros and hammocks are very different in terms of the craft.

Chinchorros are constructed from loose threads, making them elastic and light, whereas hammocks have very compact threads, giving them thickness and significantly more weight. Both types of hanging bed usually have an elaborate fringe on both sides, which is wrapped around the body to stave off the chill of the night.

Chinchorros Wayuu, together with the hammocks made in San Jacinto are the biggest and most elaborate hammocks made in Colombia and in the world.